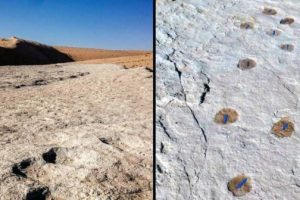

The scientists looked at the composition of residues left on fragments of ceramic pots found at six archaeological sites in the Swiss Alps. The shards of pottery were known to date from Neolithic times to the Iron Age.

They found that the residue on those from the 1st millennium BC had the same chemical signatures associated with heating milk from animals such as cows, sheep and goats, as part of the cheesemaking process.

The ceramic fragments were found in the ruins of stone buildings similar to those used by modern alpine dairy managers for cheese production during the summer months.

Although there is earlier evidence for cheese production in lowland settings, until now virtually nothing was known about the origins of cheesemaking at altitude due to the poor preservation of archaeological sites.

“The development of alpine dairying occurred around the same time as an increasing population and the growth of arable farming in the lowlands,” the scientists said.

“The resulting pressure on valley pastures forced herders to higher elevations.”

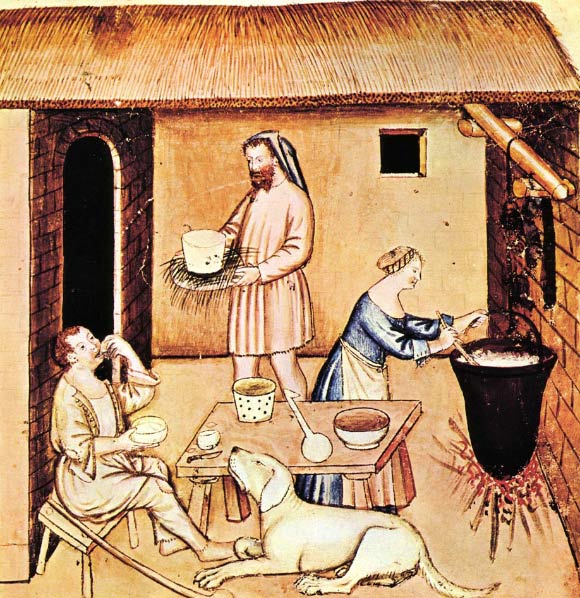

“Even today, producing cheese in a high mountainous environment requires extraordinary effort,” said lead author Dr. Francesco Carrer, of Newcastle University.

“Prehistoric herders would have had to have detailed knowledge of the location of alpine pastures, be able to cope with unpredictable weather and have the technological knowledge to transform milk into a nutritious and storable product,” he added.

“We can now put alpine cheese production into the bigger picture of what was happening at lower levels.”

“But there is more work needed to fully understand the prehistoric alpine cheesemaking process such as whether the cheese was made using a single milk or a blend and how long it was matured for.”