Photograph by Robert Clark, National Geographic

rom temples to pyramids to statues, ancient techniques moved giant blocks.The temple of Angkor Wat, the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, and the famous statues on Easter Island were all built without the conveniences of modern technology. Ancient peoples didn’t have access to forklifts, hydraulic cranes, or flatbed trucks. So how did they build the temples and statues that we admire today?

In some cases, all they needed was rope, a little manpower, and some ingenious carving. Other construction projects required harnessing the seasons, people, and animals to transport stone blocks weighing many tons to construction sites.

A new study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that ice roads lubricated with water enabled workers in 15th- and 16th-century China to slide stone blocks to Beijing in order to build palaces in the Forbidden City. (See “Beijing’s Forbidden City Built on Ice Roads.”)

Making nature work for them is a common theme in the techniques experts think ancient peoples used to build their monuments and temples.

“We forget that ancient people are just as smart as we are,” said Terry Hunt, an archaeologist at the University of Oregon who studies the Polynesian culture of Easter Island. “In fact, they may have been better focused because they didn’t have our distractions.”

Here are some of the ingenious ways in which ancient workers hauled, slid, and walked the huge stone pieces needed for their big engineering projects from quarries to construction sites.

Easter Island Statues

Harnessing physics and gravity may help explain an enduring Polynesian myth about how the stone statues of Easter Island (map), otherwise known as moai, “walked” from the quarries to the coast.

Erecting stone statues is common in Polynesian cultures as a way of paying respects to the ancestors, said Carl Lipo, an archaeologist at California State University, Long Beach.

When Polynesians first arrived on Easter Island—or Rapa Nui—in the 1200s, they brought the practice with them. They carved and erected the moai pretty much from the time they arrived on the island until sometime between 1722, when Europeans first arrived, and 1774, said Lipo.

But how they managed to move statues carved from volcanic rock—weighing 5 to 80 tons (4.5 to 73 metric tonnes)—the 6 to 8 miles (10 to 12 kilometers) from a quarry to their resting places has been a contested subject for some time.

Theories range from simply dragging the moai to a display area, or ahu, to mounting them on a kind of sled and rolling them on tree trunks. (Watch a video demonstrating some of these theories.)

One hypothesis, put forth by noted researcher, author, and National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Jared Diamond, posits that Easter Island residents used a kind of “ladder” to help transport their statues.

First suggested by Jo Anne Van Tilburg at UCLA, the ladders consisted of two wooden rails attached by fixed crosspieces that were laid down on the ground. In Diamond’s book Collapse, he describes how the Rapanui would lash a statue to a wooden sled and then slide the entire package along the ladder to the display areas.

Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl and Czech engineer Pavel Pavel have both suggested the moai walked from the quarries to the ahu in the mid-1900s and in 1990. But in 2011, Lipo and Hunt published a fleshed-out explanation of their hypothesis about how, rather than being dragged in one way or another, the statues of Easter Island were walked to their destinations.

In their book The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island, they argue that the shape of unfinished statues—with their forward-leaning bellies and D-shaped bases—would have allowed people to rock a statue from side to side as it tipped forward. It’s similar to how one might rock a refrigerator across the floor, said Lipo.

“As we walk, we tip our center of mass forward and catch our fall,” he explained. “As the statues [are] leaned forward, they tip and take a step forward.”

In 2011, funded by a grant from National Geographic’s Expeditions Council, Lipo and Hunt demonstrated this movement with a ten-foot-tall, five-ton replica statue and a team of 18 people.

They were able to walk their statue 330 feet (100 meters) in 40 minutes. The Rapanui probably could have gone across the island with a statue in a matter of weeks in this fashion, said Lipo.

Once a statue arrived at an ahu, Hunt and Lipo believe workers would refashion the base so that the monolith could stand on its own. They would also add eyes and, on some of the statues, a headpiece.

One of the more surprising things, according to Hunt, was how easy it was once the team of people got the statue rocking. “It sort of starts walking itself,” he said. “It’s a little eerie—this multi-ton thing is walking and we’re not trying very hard to make it move.” (Read about Easter Island in National Geographic magazine.)

Temple of Angkor Wat

The seat of the Khmer kingdom from the 9th to the 15th centuries, the ancient city of Angkor—in what is now Cambodia—is perhaps best known for the temple of Angkor Wat. (See the city of Angkor in 3-D.)

“Angkor Wat is only one temple among others,” said Christophe Pottier, an archaeologist and architect with the French Institute for Asian Studies in Bangkok and an expert on the ancient city.

But it is the largest temple, and its design is heavily influenced by Indian and Chinese cultures, he explained.

Trade relations with India and China ensured they left their mark on the Khmer, said Pottier. “Angkor is really at the crossroads of two giant civilizations, and [the Khmer] benefited from both.”

Indian religion played a prominent role in the design of many of Angkor’s temples, Pottier said. “They are not palaces; they are not places for the living. They were houses for gods.”

The Khmer gods lived on top of a mythical mountain called Mount Meru. And so Angkor’s temples were built as monoliths to symbolize that mountain.

The city is situated in an alluvial plain, said Pottier. So when the Khmer first started building their temples in the ninth century, they used bricks made of clay dug up from the surrounding areas.

But starting in the tenth century, they began to use stone blocks in their construction.

The quarries that produced those blocks were about 31 to 43 miles (50 to 70 kilometers) away in a sandstone plateau.

Of the blocks used in Angkor’s temples, 90 to 95 percent were between 440 and 660 pounds (200 to 300 kilograms), said Pottier. And initially, experts thought ancient workers used roads to transport the stones to the city.

But about 30 to 40 years ago, researchers identified canals linking Angkor to the quarries, Pottier explained. Most likely, the Khmer used rafts to float the blocks down to the city, especially during the rainy season, he said.

“During the dry season, [they] would have concentrated more on carving the blocks and assembling them.”

Once the blocks reached construction sites in Angkor, workers could have rolled the stones on wooden rollers for short distances, the archaeologist explained. A system of scaffolding, levees, and pulleys likely enabled the Khmer to position the blocks while constructing their temples, Pottier added. (Learn more about the city of Angkor in National Geographic magazine.)

Stonehenge

It seems the mysteries surrounding this Stone Age monument are endless. But one of the more down-to-Earth questions that has tugged at the imagination of experts, and the public, is how early Britons managed to move the monument’s enormous stones into place. (Related: “Stonehenge Revealed: Why Stones Were a ‘Special Place.'”)

Two main kinds of stone were used to build Stonehenge: bluestones, which make up the monument’s inner ring, and sarsen stones, which populate the outer ring. (Explore the different stages of Stonehenge.)

“The sarsens were moved about 40 to 50 kilometers [25 to 31 miles] from essentially local sources,” wrote Timothy Darvill, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University in Dorset, England, in an email.

They were most likely moved over land routes mounted on sleds, which then slid across rollers or rails, he explained. “Plenty of experiments have been done to show this is possible.”

Some of the bigger sarsens weigh about 40 tons (36 metric tonnes) and would need about 150 people to pull them along, Darvill added.

Michael Parker Pearson, an archaeologist at University College London—and a National Geographic grantee—notes that the roller method of transport can be problematic.

“Most of the Stonehenge sarsens weigh about 20 tons [18 metric tonnes] or more,” Pearson wrote in an email. Their weight would have squished any rollers into the turf under them.

And sliding the stones on rails can be slightly unstable, he added.

Pearson’s favorite theory is that stone-carrying sledges slid along logs lubricated with water. Such a method appears in Egyptian and Mesopotamian depictions, although Pearson doesn’t think there is any connection between Stonehenge and Egypt or Mesopotamia.

Bournemouth University’s Darvill notes that the bluestones, sourced 155 miles (250 kilometers) away in Wales, needed to travel much farther along different routes to Salisbury Plain (map).

“There are various route options, but all involve crossing major rivers or using the sea routes around the coast,” he said. Experiments show that even the largest bluestones, which weigh in at 4 tons (3.6 metric tonnes), could travel waterways via rafts.

Pearson added that ice routes would not have been an option in Britain. “I receive hundreds of queries about moving Stonehenge’s megaliths on ice,” he said.

“This method was apparently used in medieval China, but the climate of Neolithic Britain—slightly warmer than today—was nowhere near cold enough for long enough for this to be realistic.” (Read about Stonehenge in National Geographic magazine.)

Egyptian Pyramids

Theories abound on how ancient Egyptians moved the enormous limestone and sandstone blocks into place for their pyramids. But how did they transport these blocks, some weighing hundreds of tons, from the quarries to the construction sites?

“They would use the Nile whenever possible,” said Per Storemyr, a geoarchaeologist with Archaeology and Conservation Services in Brugg, Switzerland, and an expert on ancient Egyptian quarries.

“Mainly quarries in ancient Egypt were located along the Nile, so the transportation distances were relatively short,” he explained.

But for quarries located tens to hundreds of miles from construction sites, ancient Egyptians probably used a combination of manpower, sleds and rollers, and waterways to transport their building materials, Storemyr said.

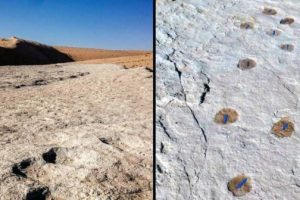

Basalt quarries in Egypt’s northwestern Faiyum desert (map), about 31 to 37 miles (50 to 60 kilometers) southwest of Cairo, produced blocks that weighed up to ten tons (nine metric tonnes).

In the Old Kingdom, about 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, workers would wedge a block out of the side of a Faiyum quarry and let it fall onto a paved road, explained Storemyr. The road wended its way southward for seven miles (12 kilometers) until it reached a now-dried-out lake that connected to the Nile River.

Workers would then take their stone block up the Nile to the intended construction site.

“It’s very difficult to find out how they transported stones on the roads,” Storemyr said. Wooden rollers work over short distances, but they’re “totally impractical for long distances,” he added.

“What we think is they made some sort of railway,” Storemyr explained. “Not a railway in the sense we know today, but some type of wood with fixed beams that a sledge that the stone is mounted on could be dragged on.”

Then it’s just a matter of “lots of people, lots of rope, lots of animals,” he added.

The railway, mounted on top of the paved road, would enable workers and animals to lug a stone on top of its sled to the lake and, eventually, up the Nile to the emerging pyramids. (Learn about the pyramids at Giza.)

Jane J. Lee

National Geographic

Published November 6, 2013