Visitors to the temple will now descend through steep, black stone-lined stairs, in Bloomberg’s new European headquarters, to seven metres below the city streets where in Roman times the smelly river Walbrook once flowed sluggishly through marshy ground. In approximately 240AD, the Romans built a temple next to the river to one of their most mysterious cult figures, Mithras the bull-slayer.

The virile young god from the east was beloved of soldiers who worshipped him by the light of flaring torches in underground temples, where the blood of sacrificial animals soaked into the mud floor. The reconstruction of his rites includes the soundtrack of shuffling sandalled feet and voices chanting in Latin the names of the levels of initiates taken from graffiti on a temple in Rome: the god still guards many of his secrets.

“It was a mystery cult and its rites remain very well guarded mysteries. There is nothing written about what went on in the temples, no book of Mithras,” said Sophie Jackson, the lead archaeologist from the Museum of London Archaeology who has spent years working on the excavation and reconstruction.

“The one thing we do know is that no bulls were sacrificed there. It was a very confined space and I don’t think anyone would have got out alive.”

The temple was a sensation when it was discovered in 1954 and swaths of London still lay in ruins after the war, but its redisplay was generally regarded as one of the most disappointing tourist sites in the city, with all the mystery of a suburban front garden.

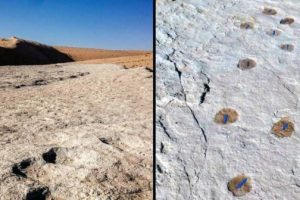

The site was identified as a Mithraeum when in the last hours of the excavation the carved head of a handsome young god was found. A newspaper photographer happened to be nearby and as the word spread thousands joined queues that stretched for half a mile around the block, waiting patiently to view the muddy foundations.

The public excitement and the keen interest of the then prime minister Winston Churchill forced Legal & General to abandon plans to demolish the foundations to make way for its grim new office block. Instead, after eight years in storage in a builder’s yard, in 1962 the walls were partially reconstructed 100 yards from the original site, inaccurately and incorporating new stone brought in to fill gaps and material lost over the years. The god’s head and other beautiful carvings went to the Museum of London and the original timber benches, which archaeologists now regard as rare treasure, were thrown away.

Bloomberg’s European headquarters, designed by Lord Norman Foster, stands on one of the richest archaeological sites in London – by one estimate a 10th of the Roman objects on display in the Museum of London come from a century of excavations on various patches of the land. Much was destroyed by the excavations of deep basements of later buildings, but where the archaeological layer survived, the soggy ground led to startling preservation, including hundreds of wooden tablets faintly preserving the oldest handwritten documents ever found in Britain, from the first years after the Roman invasion, including the first recorded use of the world Londinium.

Michael Bloomberg, the founder of the company, said they were stewards of the ancient site and its artefacts. “London has a long history as a crossroads for culture and business, and we are building on that tradition.”

The Mithraeum incorporates a new daylit art gallery at ground level with an opening installation, Another View from Nowhen, by the Dublin artist Isabel Nolan. A huge glass case displays more than 600 of the 14,000 objects found on the site, including a wooden door, a hobnailed sandal, a tiny gladiator’s helmet carved in amber, and a wooden tablet with the oldest record of a financial transaction from Britain.

London Mithraeum, at Bloomberg SPACE, will open every day except Monday from 14 November. Entrance is free but advance booking is advised.